Part 4: Misperception

The brain doesn't like being wrong...

Remember a time when you were absolutely certain that what you were seeing or hearing was real only to realize later that you were mistaken. Were you fooled by a trick of the light or by sounds that you misheard? Think about how certain you were at first and what it felt like when your perception changed. Notice the confusion you feel the next time this happens...

“Watch out for the garbage can,” Em said for the third time while I was wheeling my way down the hospital corridor. The small can was in my path on the left. I could avoid it by making a slight adjustment to my trajectory.

“It’s okay. I see it,” I assured her. I did see it, and I also saw it tip over and roll to the ground as I crashed into it. My brain couldn’t properly process anything that was on the left side of my field of vision. I could see what was there, but my body didn’t respond correctly. Someone standing on my left would be ignored unless I was prompted to pay attention to them.

My physical deficits were obvious, but the unnoticed cognitive damage surprised me when it presented itself. I wasn’t aware that I had perceptual problems until faced with them through actions or the inability to act.

When I got back to my room, the occupational therapist was there to help me relearn how to dress myself. A shirt lay on the hospital bed challenging me to crack its mystery.

“Elizabeth, can you do it?” the occupational therapist asked, calling me back to the task.

I was supposed to put on my shirt, but it made no sense. I’d done this simple activity countless times since childhood, but now I was at a loss. I picked up my shirt with my functioning hand. It gave me no hints.

“Don’t worry. It’s completely normal,” the O.T. said breezily. “Your spatial skills are affected. Very common for right-sided strokes.” I gave up trying to figure out the steps that would lead to victory. The part of my brain that held the solution to the problem was either dead or buried under swelling and inflammation.

I had no idea quite how much I’d lost until I went to my first psychology session. I’d been looking forward to having someone to talk to about the emotional impact of the stroke, but the psych session turned out to be the opposite of therapeutic.

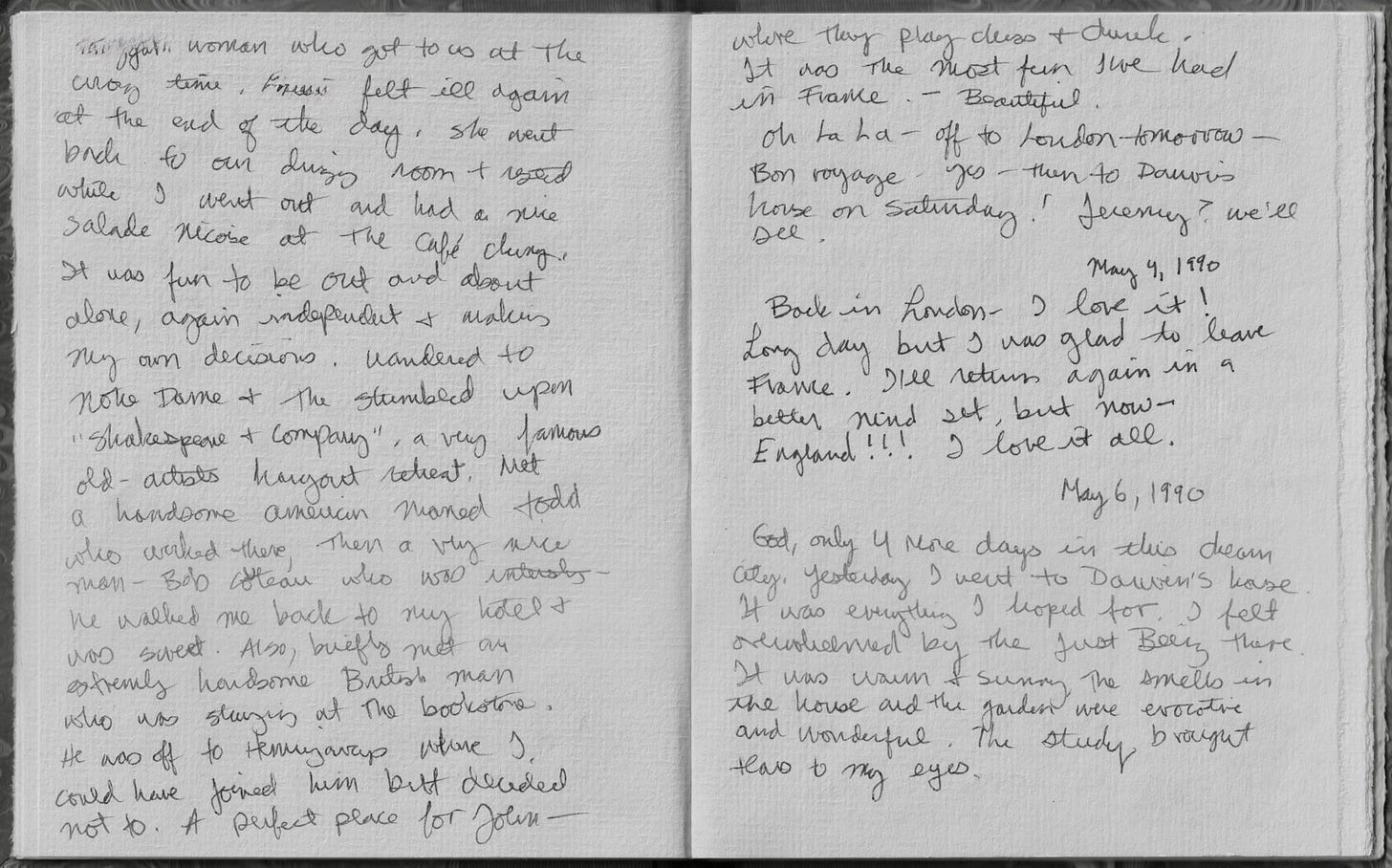

“Let’s start with this one,” Roger, the psychologist, said as I stared blankly at the red and white puzzle blocks he had laid out in front of me. The markings on the blocks looked random but Roger insisted that if I fit them together properly they’d transform into a simple geometric shape.

“This one is the easiest to solve. Take a shot at it,” he urged. Tremendous resistance to the task tightened my gut. I didn’t want to solve the stupid puzzle.

“I’ve never been good at things like this,” I said. That was only partly true. I felt frustration threatening to overtake me as I made the excuse.

“Don’t worry, just try,” Roger said. I pushed the blocks into various patterns, none of which created a geometric shape.

“What’s it supposed to be?” I finally asked, peeved. Roger had been watching me and taking notes. I finally understood. This was an assessment, not a counseling session. Psychology by way of B.F Skinner.

“Keep going,” he instructed. I gave it another reluctant try and then, with my heart pounding, I shoved the blocks away.

“I have no idea how to do this,” I said. “What shape is it supposed to make?” Roger pushed the blocks together to form a triangle. It took him three seconds. I was stunned. It was that simple? Roger put a group of more complex blocks in front of me.

“All right, let’s try these,” he said. Now I was angry. If I couldn’t make a triangle how was I supposed to figure out a more complicated shape? “Watch,” Roger said. He slowly brought the blocks together to form a rectangle. I studied his movements carefully, determined to copy his approach to the puzzle. Roger pushed the pieces apart and indicated that it was my turn. I concentrated as hard as I could, but it was no use. I couldn’t make the rectangle. Roger remained neutral in the face of my agitation. He finally put a kiddie jigsaw puzzle in front of me and told me to work on it until the end of the session.

Fragments of bunnies and carrots provided no relief. They were in league with the geometric shapes, resisting my efforts to transform them into satisfying, friendly forms.

Time for speech therapy. It was a good thing Ginny, the therapist, was such a warm, pleasant woman, because the tests she administered were the stuff of nightmares.

“Here we go,” she smiled as she pressed play on her diabolical tape recorder. Cue the stream of inane chatter, clatter of silverware, snatches of laughter and mumbled conversation. Even worse was the tape featuring numbers robotically repeated backward, forward, backward, forward.

“52, 51, 50, 7, 9, 11, 11, 9, 7, 112, 113, 114, 52, 51…” the disembodied torturer droned on and on while I tried writing answers to questions about dull stories I’d been forced to read.

“Shut up! Shut up! Shut up!!!” I silently screamed. Then the commotion turned into bells and whistles in the wake of the number sets. Ginny calmly measured how well I was able to tune out the distractions while reading and writing. It was bad. Really bad. So bad that my sister, sitting in on a session featuring the “shrieks and clangs” tape, suddenly bolted out of her chair and fled the room.

“No one can take this even without brain damage!” she blurted out as she shut the door behind her.

Ginny gave me a series of paragraphs presented out of order that were supposed to recount a brief history of Billy the Kid. I read them through a few times, but they seemed very poorly written. I launched into a critique, certain that I had a valid point to make.

“This whole thing isn’t very clear. None of the paragraphs fit together smoothly.”

“Oh?” Ginny said. “You might be right about that. Don’t worry though, just do what you think works best.” After a struggle I finally came up with an order that seemed close enough.

“Is this some kind of trick test to see if I can spot bad writing?” I asked, sliding the paper toward Ginny. “It has to be.”

“I’m sure what you did is fine,” Ginny assured me.

A few weeks later, Ginny had me read the story about Billy the Kid again. It was perfectly well-crafted and the paragraphs fit together logically. Then Ginny showed me my previous attempt at reconstructing the tale. I couldn’t believe the jumbled way I’d put it together. Now that the swelling around my brain had lessened, I easily assembled the story in the correct order. It was frightening how certain I’d been that the problem was with the writing, not my perception. There was no way you could have convinced me otherwise.

Now that I’d healed a bit, Roger’s awful red and white blocks no longer mocked me. The triangle was a snap, and although the other shapes were more challenging, at least I could figure them out.

Roger taught me a technique called “verbal mediation” to help me cope with my spatial deficits. I carefully broke up the task into smaller increments, then told myself out loud: “This is a red triangle, and you have to create a new triangle,” or “This is a red square, and you have to create a new square.” Then on to the next step. “Put this red block next to the white block. Put this white block next to the other white block.” I concentrated on the individual pieces, then pulled back when I was done to find that I’d made a whole shape.

Verbal mediation helped me deal with one of the most turbulent after-effects of the stroke: the terror of having it happen again. I used it when panic rose in my body triggered by a small ache in my temple, a moment of blurry vision, the edge of sleep that mutated into fear of losing consciousness. I calmed my racing heart and trembling limbs by speaking out loud:

“You’re okay. You’re safe. It’s over. You’re here. You’re alive. You’re safe.” I self-soothed with each utterance, fully aware that safety was a concept I’d never take for granted again.

It's not even remotely the same, but AI pisses me off by trying to pass itself off as reality. I can only imagine how frustrating it would be to have your own brain doing it. My Mom had a small stroke. The only really noticeable thing was her writing. It was super small, so she'd have to imagine she was writing hugely for it to be legible and it always got smaller as she went. Our brains are both amazing and terrifying... thank you for sharing this. It's helpful for those of us who haven't experienced a stroke first hand, but I can only imagine that it would be even more so for those who have.

I agree completely with Lisa’s comment … when one has not actually experienced this … we can only imagine what it might be like! However … your putting this experience so plainly into words truly helps us Know Better what you went through!! How Very Overwhelming and Absolutely Frustrating it was!!! I would have been screaming 4 letter Very Naughty Words!!! You know me and my mouth! 🙄🫣🤭😬

Once again Thank You for sharing this with us!!! 🙏🏻😉☺️💗💞💗💫